Nucleation and growth of a new phase

Thermally activated diffusional transformations produce the nature and quantity of phases indicated by the phase diagram if they occur at very low rates \((1 {\rm \, °C . h^{-1}})\).

Industrially, and for reasons of cost, transformation rates are much higher. Often, a state of stable equilibrium is not reached. Furthermore, for industrial alloys that often contain 5 to 15 alloying elements, the most stable state is unknown (we are able to completely define it for binary and ternary alloys).

Generally, a new phase develops within a parent phase by nucleation and growth.

Take, as an example, the liquid to solid equilibrium. During solidification (\(\ce{L -> S}\)), the structures that develop, that depend on the transformation conditions (rate, temperature) have a large influence on the final properties of the materials, irrespective of subsequent production stages. The main parameters that depend on solidification conditions are:

grain size

grain orientation

size of second phase particles

dispersion and distribution of these particles

distribution of alloying elements

At equilibrium \(\ce{L <-> S}\) (at solidification temperature \(T_S\)), free energy in liquid \(G_L\) is equal to free energy in solid \(G_S\). For solidification to progress (exothermic reaction), latent solidification heat \(L\) must be extracted from the system. Indeed, for solidification to occur, it must be that \(\Delta G < 0\), in other words \(G_S - G_L < 0\).

At \(T \neq T_S\), \(\Delta G = - \frac{L \left( T_S - T \right)}{T_S}\),

the solidification condition is written as: \(\Delta G < 0\Leftrightarrow T_S - T > 0 \Leftrightarrow T < T_S\)

\(T_S - T\) is called undercooling, it is the driving force for solidification. It is a metastable state of a body that stays liquid below its solidification temperature.

Statistically, in a liquid there is a short distance order. Momentarily and locally, clusters of atoms can exist with the structure of the solid. These clusters remain unstable if \(T > T_S\) and becomes stable if \(T < T_S\). These are nucleation sites or nuclei, they are spherical in shape.

Conditions for the appearance of stability in spherical nuclei

Thermodynamically, a volume \(V\) of liquid transforms to solid if the free energy in the system decreases: \(\Delta G = \Delta G_\textrm{volume} + \Delta G_\textrm{surface} < 0\).

For a spherical nucleus,

\(\Delta G = \frac{4}{3} \pi R^3\Delta G_V + 4 \pi R^2 \gamma _{LS}\) ,

with \(R\) the nucleus radius, \(\Delta G_V\) the formation energy of the new phase by unit of volume (negative term) and \(\gamma_{LS}\) the superficial energy of the interface (positive term).

At point of equilibrium, the critical radius can be calculated by noting that:

\({\left( \frac{d\Delta G}{dR} \right)}_{R^\textrm{*}} = 0 \Leftrightarrow R^{\textrm{*}} = - \frac{2 \gamma _{LS} }{\Delta G _V} = \frac{2 \gamma _{LS} T_S}{L \left( T - T_S \right) }\)

If the nuclei are present in the liquid at a given instant, their evolution depends on their radius. If \(R > R^{\textrm{*}}\), then \(\Delta G\) diminishes and the nuclei develop, if \(R < R^{\textrm{*}}\), then \(\Delta G\) increases and the nuclei dissolve. \(R^{\textrm{*}}\) is inversely proportional to undercooling. In the case of \(\ce{Cu}\) for example, \(R^{\textrm{*}} = {0,01}{\rm \, \mu m}\) corresponds to an undercooling of \({30}{\rm \, °C}\) and \(R^{\textrm{*}} = {1}{\rm \, \mu m}\) corresponds to an undercooling of \({0,3}{\rm \, °C}\).

Nucleation rate

Nucleation has occurred if, and only if, nuclei of a supercritical size form (\(R > R^\textrm{*}\)). They result from fluctuation (random atom movements) provoked by thermal agitation. The number of nuclei with radius \(R^\textrm{*}\) at temperature \(T\) is given by the relationship:

\(n \left( R^\textrm{*}\right) = \textrm{C}^\textrm{ste} \cdot \exp \left( \frac{- \Delta G^\textrm{*}}{kT} \right)\)

The nucleation rate is exponentially dependent on temperature.

Heterogeneous nucleation

Critical radius corresponds to a grouping of around 100 atoms and would correspond to undercooling of \({100}{\rm \, K}\). However, in practice, few degrees are sufficient to initiate the phase transformation. We can conclude that homogeneous nucleation is unlikely and that another mechanism is operative: this is heterogeneous nucleation.

This type of nucleation occurs on a solid substrate, which acts as catalyser for germination, as shown in the following figure.

The expression of \(R^\textrm{*}\) is unchanged but volumes involved are different. Statistical fluctuation gives the same probability that \(N\) atoms will group within the liquid rather than on a wall, but the grouping of these \(N\) atoms corresponds to a larger radius when they are arranged in a spherical cap rather than a sphere.

The wall can be that of the recipient containing the liquid (mould), an emerged solid (addition of impurities known as inoculants to reduce grain size: \(\ce{Ti}\), \(\ce{B}\) in \(\ce{Al}\) or \(\ce{Zr}\) in \(\ce{Mg}\) or ferrosilicon on cast steels). When the parent phase is solid, the wall might be a grain boundary, a dislocation, or the surface of other phases already present in the material.

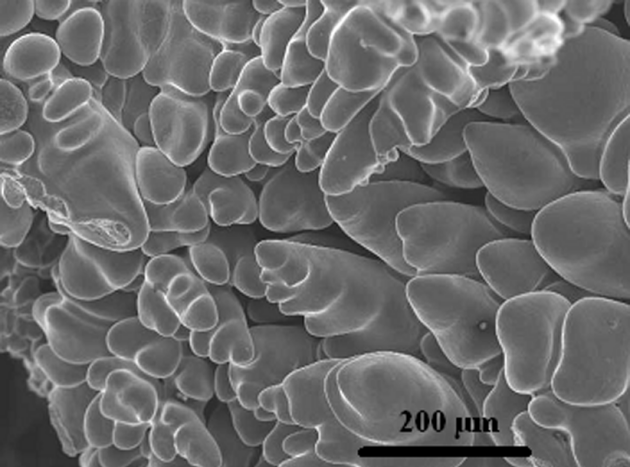

When solidified, solid nuclei are not spherical but grow in shapes that relate to their crystalline system: these branching grains are called dendrites and are illustrated below.