Introduction

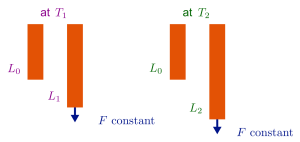

Creep corresponds to a deformation generated by a combination of three elements acting concomitantly on the material: temperature, time and stress. The stress is lower than the yield strength of the material and the temperature is generally constant. Creep is similar to fatigue in that it provokes irreversible damage in the material. The difference between these two types of damage lies in the fact that with fatigue it is cracking that provokes fracture, whereas with creep it is the deformation. Phenomenologically, if we subject a material to a given stress, below its yield strength, and if the temperature remains below half its melting temperature (expressed in Kelvin), the strain imposed is recovered entirely when the load is removed. The material is strained within the elastic domain. Above this threshold temperature, permanent residual deformation is observed in the precise case where the stress applied and/or the duration of application of the load are sufficient (see figure). The material is strained under conditions where creep occurs: application of constant stress leads to deformation which evolves over time and can lead to fracture.

Straining in the elastic domain

Force \(F\), i.e. stress \(\sigma\), is constant

At \(T_1\), there is no permanent deformation (no creep)

At \(T_2\), the length of the test piece increases with time until fracture (creep)

The temperature threshold is \(T = 0.5 T_m\) (in Kelvin).

Creep reflects the behaviour of materials at high temperatures, unlike visco-elasticity which leads to no permanent deformation and no fracture (see following figure).

A few examples:

Creep in lead pipes at room temperature as a result of their own weight. The melting temperature of lead is \(T_F = {600}{\rm \, K}\), creep can occur above \({300}{\rm \, K}\) (\({25}{\rm \, °C}\)).

(NB : room temperature is a high temperature for \(\ce{Pb}\))

Creep in the tungsten filaments of lightbulbs. The melting temperature of tungsten is \(T_F = {3695}{\rm \, K}\) \(({3422}{\rm \, °C})\) and the service temperature of filaments in a lightbulb is \(0.7 T_F\) \(({2400}{\rm \, °C})\). Creep occurs and is reflected in a colapse of the spires of the filament, leading to a short-circuit.

(NB: \({1000}{\rm \, °C} - {1500}{\rm \, °C}\) are low temperatures for \(\ce{W}\))

Creep in glaciers (\({-20}{\rm \, °C}\) / \({-30}{\rm \, °C}\)) and pack ice \(({-40}{\rm \, °C})\). The ice melts at \({0}{\rm \, °C}\) (\({273}{\rm \, K}\)). At \(0.5 T_F = {135}{\rm \, K}\) (\({-130}{\rm \, °C}\)), creep occurs and is reflected in displacements.

(NB: \({-20}{\rm \, °C}\) / \({-40}{\rm \, °C}\) are high temperatures for ice.)

Creep in jet engines turbine blades. Blades are manufactured from a nickel-based superalloy \((T_F = {1400}{\rm \, °C})\) and work between \({800}{\rm \, °C}\) and \({1100}{\rm \, °C}\), under the effect of centrifugal forces relating to the rotation of the engine that generate constant stresses. Blades fail because of creep and they are specifically designed to resist this type of damage (see figure).

Creep in aluminium air foils used in supersonic aircraft (see following figure). An aircraft's lift is provided by the pressure difference \(\Delta P\) established between the low pressure provoked by the rapid upper wing surface air flow and the high pressure provoked by the slow lower wing surface air flow. The wedge of static air that moves with the aircraft is warmed by frictional forces between the two air flows and the temperature is \(T_A = T_0 (1 + 0.2 M^2)\). For an external temperature \(T_0 = {-55}{\rm \, °C}\) and a speed of Mach 2, \(T_A = {120}{\rm \, °C}\). This is a domain where the risks of aluminium creep are real, and as a consequence supersonic structures are built from titanium.